Guest posts are intended as first-person windows onto contributors’ journeys to make a life in writing.

by Ariel Fintushel

Part I. From Double Shifts to Graduate School

As I write this, there is a partial Full moon eclipse in Aquarius which means something is being excavated. A hand – is it mine? – reaches in and extracts: what will you let go of and what will you become?

In between double shifts as a barista and as a waitress in a Middle Eastern restaurant serving soggy aram rolls, I read Rob Breszny’s horoscope column in the Bohemian newspaper. These are ridiculous, I think to myself, I’d do a better job. It reminds me of what Bukowski said, “When I begin to doubt my ability to work the word, I simply read another writer and know I have nothing to worry about.”

It was the year after I graduated from UC Santa Cruz with a B.A. in Global Literature. I thought I might travel to Thailand to live in a monastery or trek in wild landscapes, but instead I moved back home, got a small apartment with my boyfriend, and worked. I found a copy of Wang Ping’s The Magic Whip and Kim Addonizio’s Tell Me in the local library and would read at night, dreaming of a way to escape customer service: “When asked where I’m from,/ I say ‘Weihai,’ even though/ nobody knows where it is,/ even though I’ve never been to that place” (Wang Ping from “Mixed Blood”). I started wearing someone else’s name tag: “Mariah, it means wind,” a customer told me.

When I learned I was accepted to SF State’s MFA program as a poet, I had surging feelings of self-worth and even arrogance. It made dealing with snotty customers and overflowing toilets that much better. “I’m going to get my MFA and become a professor of poetry,” I told them. “Not that scone,” they replied, “the one with more blueberries on it.”

Part II. My First Class with Stacy Doris

The year I moved to San Francisco was 2009, and Jupiter in my ninth house meant my ideals were not matching up to reality. I found a house on 34th and Judah where the ocean made a steam room of the streets and rode my bike to Stacy Doris’s class for the first time. “Any poetry that doesn’t somehow begin in a realm of wild fantasy is not worth the writing,” she said. I liked her already.

The MFA is supposed to take 3 years, but because I took every class Stacy taught regardless of whether I needed the credit, it took me four. Her classes were workshops for collaboration where we listened with a meditator’s focus investigating the nature of sound and its implications for our writing. They were experiential classes, and we traversed the campus banging garbage cans and cataloguing the noises it could make. Once Stacy led us through Union Square and Chinatown where we recorded a parade, an opera in the alley, wind chimes, and the Blue Angels in order to make sound compilations exploring the phenomenon of interruption.

Stacy was my advisor, but she was also a friend. When my boyfriend broke up with me over Christmas, she said, “You’ll meet someone fun.” We got soup at Judahlicious, and she showed me her poem, “A Month of Valentines”: “To my Love Supreme// from her little/ lotus flower: Bud/ stamen and leaf/ my heart only beats/ with hope of your/ touch./ Kevin.” or “Red Rose:// All leather, rare/ flowers/ your cavelier lips/ my ponytail puff/ to dinosaur shape./Let’s fuck.// Ph.D.”

Part III. The Graduate Thesis

When Stacy passed away from a rare cancer affecting her smooth, involuntary muscles, Camille Dungy became my advisor. While Stacy told me, “I see a book in here,” Camille asked important and difficult questions: “what’s at stake” and “where are you in all this?” Many of Stacy’s students felt suddenly lost and abandoned. Like one of her beloved disciples said, “Now the world is just a little bit shittier.”

Instead of “When where am I is I,” I took Camille’s class, Literary Mapping. I tried to write things that were more personal but sometimes felt like I was trying to dredge up traumas that did not exist. “Sometimes what is neutral is most powerful,” she suggested.

I focused on learning to teach. With two sessions of my own 25 person Introduction to Creative Writing class, I was overcome with excitement that also manifest as anxiety. If one student looked bored, my whole world ended.

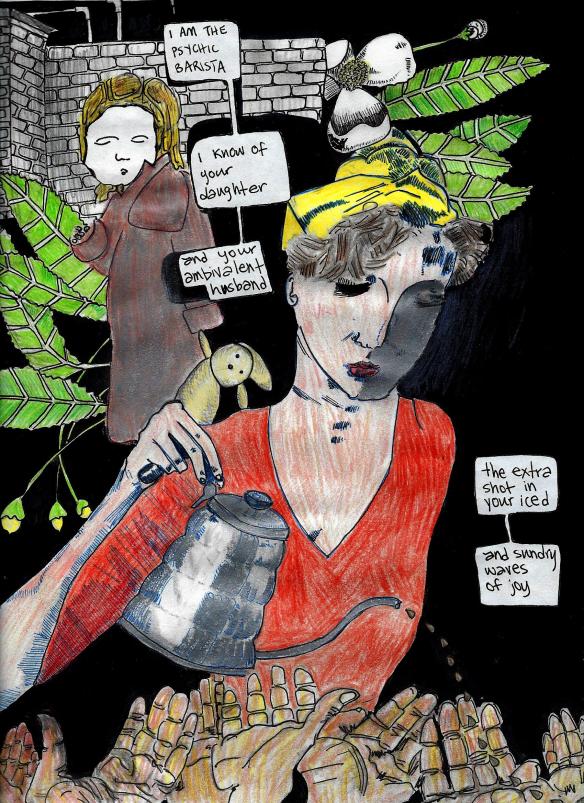

In the meantime, my graduate thesis was a slurry of writing including illustrated comics inserted on a whim to make things feel more coherent. I was not disappointed with my thesis because I knew there was a lot to digest between Stacy’s and Camille’s different approaches to poetry. Like Basho said, “‘To learn about the pine tree… go to the pine tree; to learn from the bamboo, study bamboo” (qtd. in The Heart of Haiku by Jane Hirshfield). Both Dungy and Doris taught me this principle, sending me out into the field to investigate my questions.

Part IV. Teaching in New York City

After my MFA, I took a chance and moved into a Queens apartment with a new love. I got a job teaching English and Literature at Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC). There I met poet Andrew Levy who gave me a copy of his book, Nothing is in Here and gave me advice over coffee.

BMCC’s small adjunct offices were packed with books and shoved you right up against your co workers encouraging conversation. I met a Syrian man with a PhD. in theater who said he had been there on September 11th, wandering aimlessly, unable to get a cab home. I met another who told me how to teach MLA citation and also buy an umbrella that would last. One adjunct told me how he supported himself by writing curriculum for tests and leading a trivia night in a metal bar.

The students at BMCC had a lot of energy. They were from all over – Haiti, Puerto Rico, Africa, the Bronx – “You have to live in the Bronx,” they told me. They wrote about dancing the Bachata and their New York identities whether immigrant or native. I made wacky essay assignments like compare Bob Marley to Salman Rushdie and defend a new set of laws for America. It was exhilarating but also exhausting. I took two trains lugging my heavy book bags through security and up six escalators to my classroom then all that in reverse on the way home.

Part V. Teaching in Los Angeles

After a year, I moved to Los Angeles and got married. I got a job teaching at the Acting, Music and Dance Academy (AMDA) and Oxnard College. I found it more difficult to meet coworkers at Oxnard and often felt lonely.

One day, during a heat wave, lugging my bags to a cafe to grade between classes, I had a thought: I’m a manual laborer. I did the math – I was making about $5.00 an hour tops if I counted lesson planning, grading, emailing and even less if I counted the commute. My back was always sore and I had to put my legs up the wall at home like when I was a barista. Also, I was always sick and had recently been to the emergency room for bouts of asthmatic coughing attacks which disrupted my lessons.

Diane di Prima said, “I wanted everything—very earnestly and totally—I wanted to have every experience I could have, I wanted everything that was possible to a person in a female body, and that meant that I wanted to be mother.” When I got pregnant, I had all-day morning sickness and used that as impetus to quit teaching in the middle of the semester. I broke out of the cycle, and that gave me a new perspective. I felt like Saturn gone retrograde had liberated my idealistic, Neptunian instincts. I lounged around for a month imagining other possible career paths.

Part VI. Life Beyond Academia

For fun, I picked up a freelance horoscope gig writing weekly and monthly sun-sign horoscopes. The pay was better than what I made as a professor. Plus, it was fun to spend time thinking about the Cosmos–I felt like the guy who burns down his house to buy a telescope with the insurance money from Robert Frost’s poem, “Star-splitter.”

Since I still had time on my hands, I volunteered with a non-profit called Women’s Voices Now writing curriculum. All of a sudden they said, hey, why not make a films and poetry workshop. Before I knew it, I was writing a grant proposal then driving alongside the ocean on Hwy. 1 to teach my first class. Stacy wrote, “Only the nerves are a sea plant we can’t gather. They spread like fire on a curtain of trees.”

Every moment I spent planning and facilitating the workshop was in honor of the residents who took my class. It felt important to publish their work, so I made them a small anthology and also a video poem where their words and voices were raised up in honor of their creations. They wrote about homelessness with the poignancy of Rumi yearning for the Beloved: “We have the Right 2 Rest/ We have no home/ Where can we go?/ Sleep at the Mayor’s house, or the Governor’s mansion?/ Will they roll out the red carpet 4 us?” (Sunshine). Where the government failed them, I hoped to offer something: a spot they could return to be themselves, to be heard respectfully and speak with dignity.

On November 18th this year there is a new Moon in Scorpio representing an intimate blossoming and reverence for mystery. Overlapped with this cosmic event, my friend and I are hosting a 3-day inaugural retreat. Participating artists and writers will encounter a series of experiential workshops to commune, engage and dialogue with the desert culminating in an anthology.

In “Song of Enlightenment” Yoka Daishi sings of the desert, “You cannot take hold of it, and you cannot get rid of it; it goes on its own way. You speak and it is silent; you remain silent, and it speaks.” Sometimes I want to pin my purpose down, or pin down a poem, but of course that ruins it. “Poetry buckles under the weight of seriousness of purpose,” Doris wrote. Even the stars and planets are constantly in transit, pummeling us with a mishmosh of intentions and forces that result in the rough and wild terrain that becomes both art and life.

Ariel Fintushel is a Los Angeles poet working as the Curriculum Developer for the non-profit Women’s Voices Now. She runs a creative writing workshop called Films & Poetry at Turning Point Shelter in Santa Monica, and has previously taught at SF State, Borough of Manhattan Community College, Oxnard College, The American Academy of Music and Dance, and is a creative writing instructor for California Poets in the Schools. She has an MFA from SF State. Her writing has been published by Huffington Post, Zaum, Baltimore University’s Welter, The A3 Review, and elsewhere. She enjoys making audio and also illustrated poems and is interested in the desert as a place of deprivation and miracles, latent energy, adventure, malice, and mysticism.